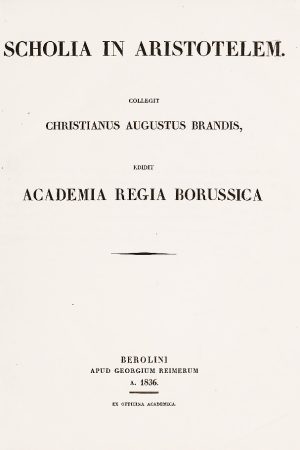

SCHOLIA IN ARISTOTELEM

- Description

Description

Scholia in Aristotelem, collegit Augustus Brandis, edidit Academia Regia Borussica, Berolini, aud Georgium Reimerum 1836

Simplicius

Simplicius (490 AC – 560 AC) was born in Cilicia in southern Anatolia which had been a Roman province from the first century BC. We know that he went to Alexandria where he studied philosophy at the school of Ammonius Hermiae.

Ammonius himself was a pupil of Proclus and Eutocius dedicated his commentary on Book I of Archimedes’ On the sphere and cylinder to him. Ammonius’s main work throughout his life was writing critical works on Aristotle and this clearly influenced Simplicius who was himself to write extensive commentaries on Aristotle.

After studying under Ammonius in Alexandria, Simplicius went to Athens where he studied with the Neoplatonist philosopher Damascius. Damascius had written Problems and Solutions about the First Principles which develops the Neoplatonist philosophy as expounded by Proclus. Again Simplicius was exposed to similar views to those he had learnt in Alexandria and his philosophy was built up in a consistent way.

Damascius had been made head of Plato’s Academy in about 520 and he was still head when the Christian emperor Justinian closed it in 529. At the same time Justinian closed all the other pagan schools. When Justinian had become emperor, his troops were fighting on the Euphrates River against the armies of the Persian king. It was therefore natural that Damascius, Simplicius and five other members of the Academy, when forced out of Athens, went to Persia to serve at the court of the Persian king Khosrow I. Khosrow was a great patron of culture and Simplicius was well received by the ruler. However, Khosrow and Justinian signed the Treaty of Eternal Peace which was ratified in 532 which led to Simplicius being able to return to Athens.

It is not entirely clear what the terms of the treaty were in regard to Simplicius and the other philosophers who had gone to Persia. Agathias, the Byzantine poet and author of a history of his own times, wrote of these events after the death of Justinian in 565. He wrote that :

… the terms of the treaty would have guaranteed to the philosophers full security in their own environment: they were not to be compelled to accept anything against their personal conviction, and they were never to be prevented from living according to their own philosophical doctrine.

The accuracy of this view by Agathias has been challenged by Cameron in [4], however, and things may not have been as easy for Simplicius after his return to Athens as Agathias suggested.

There is some evidence that Simplicius did remain in Athens for the rest of his days, writing and undertaking research but certainly not being allowed to lecture. This is reflected by the nature of his writings which are not of the lecture course style, but instead are carefully constructed interpretations of the writings of Aristotle and in particular they attempt to harmonise the views of Plato and Aristotle.

Of the writings of Simplicius that have survived, it is thought that the earliest is his commentary on Epictetus’s Enchiridion which some historians believe was written by Simplicius while he was still in Alexandria. This, however, seems highly unlikely and the argument by Cameron in that it was written during Simplicius’s time in Persia seems much more convincing. Certainly this seems to have been written before the commentaries on Aristotle, the first of which is the commentary on De Caelo. This is followed by Simplicius’s commentary on Aristotle’s Physics and both these works are particularly important for the history of mathematics.

In the commentary on De Caelo Simplicius gives a detailed account of the concentric spheres of Eudoxus and he also relates the modifications to the theory made later by Callippus. Simplicius is quoting from Eudemus’s History of Astronomy in giving these details, but he does not quote directly from that work, rather quoting from Sosigenes (who wrote in the second century AD) who in turn quotes from Eudemus.

In his commentary on Aristotle’s Physics Simplicius quotes at length from Eudemus’s History of Geometry which is now lost. In particular Simplicius quotes the writing on Eudemus on Antiphon’s attempts to square the circle and also the attempts of Hippocrates when he squared certain lunes. Also in this commentary on Aristotle’s Physics Simplicius gives important quotations from Geminus’s summary of Posidonius’s Meteorologica.

Simplicius wrote a commentary on Euclid’s Elements which survives in an Arabic translation. The commentary does not contain an attempt at a proof of the parallel postulate by Simplicius himself, despite the evidence that indeed Simplicius did attempt such a proof. There is a discussion of how Simplicius’s attempted proof of the parallel postulate entered Arabic mathematics and was first criticised, then incorporated into a new ‘proof’ designed to take the criticism into account.

Philoponus

An Alexandrine scholar of great renown, which he deserved but little on account of his extreme dullness and want of good sense, was called Φιλόπονος because he was one of the most laborious and studious men of his age. He lived in the seventh century of our era; one of his writings, Physica, is dated the 10th of May, A. D. 617. He calls himself γραμματικός, undonbtedly because he taught grammar in his native town, Alexandria, and would in earlier times have been called rhetor. He was a disciple of the philosopher Ammonius. Although his renown is more based upon the number of his learned productions, and the estimation in which they were held by his contemporaries, than upon the intrinsic value of those works, he is yet so strangely connected with one of the most important events of his time, though only through subsequent tradition, that his name is sure to be handed down to future generations. We allude to the capture of Alexandria by Amru in A. D. 639, and the pretended conflagration of the famous Alexandrine library. It is in the first instance said that Philoponus adopted the Mohammedan religion on the city being taken by Amru, whence he may justly be called the last of the pure Alexandrian grammarians. Upon this, so the story goes, he requested Amru to grant him the possession of the celebrated library of Alexandria. Having informed the absent khalif Omar of the philosopher’s wishes, Amru received for answer that if the books were in conformity with the Koran, they were useless, and if they did not agree with it, they were to be condemned, and ought in both cases to be destroyed. Thus the library was burnt. We now know, however, that this story is most likely only an invention of Abul-faraj, the great Arabic writer of the 13th century, who was however a Christian, and who, at any rate, was the first who ever mentioned such a thing as the burning of the Alexandrine library. We consequently dismiss the matter, referring the reader to the 51st chapter of Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall.” It is extremely doubtful that Philoponus became a Mohammedan. His favourite authors were Plato and Aristotle, whence his tendency to heresy, and he was either the founder or one of the first and principal promoters of the sect of the Tritheists, which was condemned by the council of Constantinople of 681. The time of the death of Philoponus is not known.

Works

The following is a list of his works: –

- Τῶν εἰς τὴν Μωυσέως κοσμογονίαν ἐξηγητικῶν λόγοι ζ᾽

Τῶν εἰς τὴν Μωυσέως κοσμογονίαν ἐξηγητικῶν λόγοι ζ᾽, Commentarii in Mosaicam Cosmogoniam, lib. viii., dedicated to Sergius, patriarch of Constantinople, who held that see from 610 to 639, and perhaps 641.

Editions: Ed. Graece et Latine by Balthasar Corderius, Vienna, 1630, 4to. The editor was deficient in scholarship, and Lambecius promised a better edition, which, however, has not appeared. Photius (Bibl. cod. 75) compares the Cosmogonia with its author, and forms no good opinion of either.

- Disputatio de Paschale,, “ad calcem Cosmogoniae,” by the same editor.

- Κατὰ Πρόκλου περὶ αἰδιότητος κόσμου λύσεις, λόγοι ιή

Κατὰ Πρόκλου περὶ αἰδιότητος κόσμου λύσεις, λόγοι ιή, Adversus Procli de Aeternitate Mundi Argumenta XVIII. Solutiones, commonly called De Aeternitate Mundi. The end is mutilated.

Editions : the text by Victor Trincavellus, Venice, 1535, fol.; Latin versions, by Joannes Mahotius, Lyon, 1557, fol., and by Casparus Marcellus, Venice, 1551, fol.

- De quinque Dialectis Graecae Linguae Liber.

Editions: Graece, together with the writings of some other grammarians, and the Thesaurus of Varinus Camertes, Venice, 1476, fol. 1504, fol.; ad calcem Lexici Graeco-Latini, Venice, 1524, fol.; another, ibid. 1524, fol.; Basel, 1532, fol.; Paris, 1521, fol.

- Συναγωγή των πρὸς διάφορον σημασίαν διαφόρως τονουμένων λέξεων, Collectio Vocum quae pro diversa significatione Accentum diversum accipiunt, in alphabetical order.

Editions : It has been often published at the end of Greek dictionaries. The only separate edition is by Erasmus Schmid, Wittenberg, 1615, 8vo, under the title of Cyrilli, vel, ut alii volunt, Joanni Philoponi Opusculum utilissimum de Differentiis Vocum Graecarum, quod Tonum, Spiritum, Genus, &c., to which is added the editor’s Dissertatio de Prouunciatione Graeca Antiqua. Schmid appended to the dictionary of Philoponus about five times as much of his own, but he separates his additions from the text.

6.Commentarii in Aristotelem

- In Analytica Priora.

Editions: Ed. : the text, Venice, 1536, fol.; Latin versions, by Gulielmus Dorotheus, Venice, 1541, fol.; Lucillus Philaltheus, ibid. 1544, 1548, 1553, 1555, fol.; Alexander Justinianus, ibid. 1560, fol.

- In Analytica Posteriora.

Editions : Venice, 1504, fol., together with Anonymi Graeci Commentarii on the same work, ibid. 1534, fol., revised and with additions, together with Eustratii, episcopi Nicaeani (who lived about 1117) Commentarii on the same work. A Greek edition of 1534 is said to exist. Latin versions by Andreas Grateolus, Venice, 1542, fol., and Paris, 1543, fol.; by Martianus Rota, Venice, 1559, 1568,

- In quatuor priores Libros Physicorum.

Philoponus speaks of his Scholia to the sixth book, whence we may infer that he commented upon the four last books also.

Editions : in Greek, the text, cum Praefatione Victoris Trincavelli ad Casparum Contarenum Cardinalem, Venice, 1535, fol.

In Latin, Latin version, by Gulielmus Dorotheus, Venice, 1539, ibid. 1541, fol.; a better one by Baptista Rasarius, ibid. 1558, 1569, 1581, fol.

- In Librum unicum Meteorum.

Editions : The text ad calcem Olympiodori “In Meteora,” Venice, 1551, fol. Latine, by Joannes Baptistus Camotius, Venice, 1551, 1567, fol.

- In Libros III. de Anima, Graece, cum Trincavelli Epistola ad Nicolaum laum Rodulphum Cardinalem, Venice, 1553, fol.

Latine, by Gentianus Hervetus, Lyon, 1544, 1548. Venice, 1554, 1568; and by Matthaeus a Bove, Venice, 1544, 1581, all in fol.

- In Libros V. De Generatione et Interitu. Graece, cum Praefatione Asalani,

Venice, 1527, fol., together with Alexander Aphrodiseus, Meteorologia.

- In Libros V. De Generatione Animalium,

Graece cum Petri Corcyraei Epistola Graeca ad Andream Matthaeum Aquavivam, Venice, 1526, fol.

Latine, by the same, ibid. eodem anno. Black letter.

- In Libros XIV. Metaphysicorum.

Latine by Franciscus Patricius, Ferrara, 1583, fol. The text was never published.

Oher works:

Εις το Α΄ των μετεώρων

Περί αστρολάβου χρήσεως

Υπομνήματα στο πρώτο και δεύτερο βιβλίο της Νικομάχου αριθμητικής (A. Delatte, Anecdota Atheniensa)

Alexander Aphrodisieus

A philosopher from Aphrodisias in Caria, follower of the Peripatetic school and one of the foremost commentators of Aristotle. He was taught Peripatetic philosophy by Herminus, a commentator of Aristotle whose works are lost, Aristocles of Messene, a Peripatetic philosopher mentioned by Galen, and by Sosigenes, who had studied Eudoxus of Knidos’s theory of the spheres.

A recently published inscription from Aphrodisias mentions his name and confirms his position in the school: Titus Aurelius Alexander, son of Alexander, also philosopher (Angelos Chaniotis, “Epigraphic evidence for the philosopher Alexander of Aphrodisias„ Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 47 (2004), pp. 79–81). This information has led some scholars to hypothesize that some of the works attributed to him were written in fact by his father. His extremely thorough and precise commentaries (hypomnemata) were higly appreciated and drawn upon by later commentators of Aristotle as well as Neoplatonists (Plotinus). His commentaries to the following works of Aristotle have survived: On Prior Analytics I, Meteorology, On Sense Perception, Topics and Metaphysics. In contrast, his hypomnemata to Physics, the Categories and other treatises of the Stagirite philosopher have been lost.

His own philosophical works that have come down to us include On the Soul, On Fate (addressed to emperors Septimius Severus and Antoninus (Caracalla), which places the work between 198 and 211 when Caracalla reigned jointly with his father Severus), and Ethical Problems. Several other works are erroneously attributed to him. Alexander taught Aristotelian philosophy in Athens between 191 and 211, and in Alexandria.

The total of Alexander Aphrodisias comments to Aristotle, are published by the Academiae litterarum regiae Borussicae between 1883 and 1901, in 7 volumes [3193]-[3198].

REF.: DNP 1, 480–482: 26 (R. Sharples), RE 1/1, 1453–1455: 94 (A. Gercke), DKP 1, 253: 21 (W. Sontheimer), HD 41

References

Soulier, Philippe, 2014, Simplicius et l’Infini, (Anagôgê), Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

Les Commentaires de Simplicius et de Jean Philopon à La Physique d’Aristote: Tradition et Innovation, (Commentaria in Aristotelem Graeca et Byzantina, 3), Berlin: de Gruyter.

Please contact us for more information here