PTOLEMAEUS 1535

- Description

Description

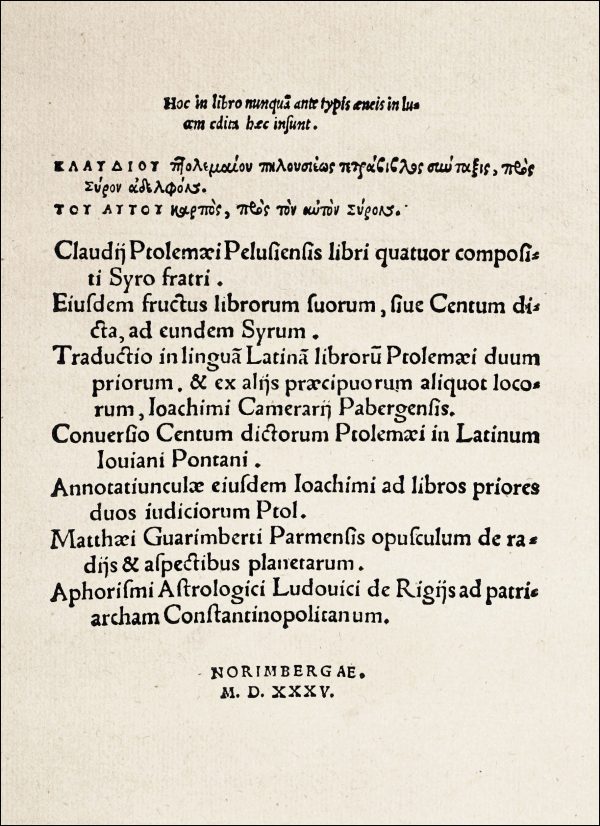

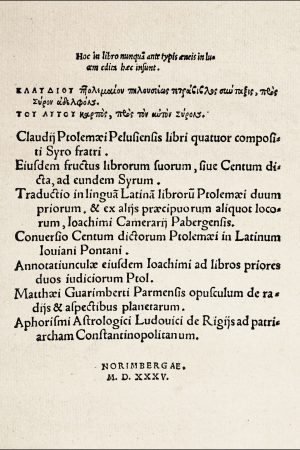

Hoc in libro nunquam ante typis aeneis in lucem edita haec insunt Κλαυδίου Πτολεμαίου πηλουσιέως τετράβιβλος σύνταξις προς Σύρον αδελφόν, του αυτού Καρπός προς τον αυτόν Σύρον – Claudii Ptolemaei Pelusiensis libri quatuor compositi Syro frattri, eiusdem fructus librorum suorum, sive centum dicta, ad eundem Syrum traductio in lingua Latinā librorū Ptolemaei duum priorum, & ex aliis praecipuorum aliquot locorum Ioachimi Camerarij Pabergensis, Norimbergae, 1535

Βιβλ.: Houzeau & Lancaster 3636 • Sotheby’s 16/11/2006 • Hoffmann III, 309 • Grässe V, 497 • EB 4525, 225 • Harles II, 154 • Schweiger 279 • Schöll V, 256 • Melies 19 • Fabricius V, 287

The very rare first Greek edition, i.e. the editio princeps of the Greek text and the first edition of Camerarius’ seminal translation into Latin (directly from the Greek), of Ptolemy’s famous textbook of astrology known under the name “Tetrabiblos” or “Quadripartitum”, derived from its four books, the work which “ranks as the Bible of Astrology” (Stillwell) and which Ptolemy himself considered the natural complement to his “Almagest”: “as the latter enables one to predict the positions of the heavenly bodies, so the former expounds the theory of their influences on terrestrial things.” (D.S.B. XI:198). The present edition also contains the editio princeps of the Greek text of the “Karpos”, or “Centiloquium” (because of its 100 aphorisms), erroneously attributed to Ptolemy. The “Tetrabiblos” is considered one of, if not the, most important surviving ancient texts on astrology, and its impact and influence on this field has been immense. It was by far the most popular astrological work of Antiquity and it also greatly influenced the Islamic world, the Medieval Latin West, and the Renaissance. It was reprinted continuously for centuries, and its great popularity is often attributed to the fact that it is a textbook on the art of astrology itself and a “scientific” defense of it rather than a mere manual instructing lay people on how to practice the art. “Of Ptolemy’s genuine works the most germane to and significant for our investigation is his “Tetrabiblos”, “Quadripartium”, or four books on the control of human life by the stars. In the “Tetrabiblos” the art of astrology receives sanction and exposition from perhaps the ablest mathematician and closest scientific observer of the day or at least from one who seemed so for succeeding generations. Hence from that time on astrology was able to take shelter from any criticism under the aegis of his authority.” (Thorndike I:111).As opposed to the “Karpos”, almost all research points to the fact that the “Tetrabiblon” must genuinely be by Ptolemy, and as such, it is to be considered of the greatest importance, not only to astrology, the history and impact of the science, but also to astronomy and to the understanding of the man who wrote one of the most important astronomical works of all times. In the “Tetrabiblos” Ptolemy first discusses the validity of the art of judicial astrology, and the introductory chapters are devoted to defending astrology against charges that it is uncertain and useless. According to Ptolemy, the laws of astronomy are beyond dispute, but the art of predicting human affairs from the movement of the stars should be attacked using more reason than that, and his main argument is that one should not reject the art itself merely because it can be abused, and frequently is, by impostors, or because it is an art not yet fully developed and may be difficult to handle properly. In book I Ptolemy goes on to explain the technical concepts of astrology, in book II, the influences on the earth in general, and in books II and IV, the influences on human life. “Although often dependent on earlier authorities, Ptolemy often develops his own dogma. The discussion in books III and IV is confined to what can be deduced from a man’s horoscope.” (D.S.B. XI:198). “The great influence of the “Tetrabiblos” is shown not only in medieval Arabic commentaries and Latin translations, but more immediately in the astrological writings of the declining Roman Empire, when such astrologers as Hephaestion of Thebes, Paul of Alexandria, and Julius Firmicus Maternus cite it as a leading authoritative work. Only the opponents of astrology appear to have remained ignorant of the “Tetrabiblos”, continuing to make criticisms of the art which do not apply to Ptolemy’s presentation of it or which had been specifically answered by him.” (Thorndike I: 115-16).

Hübner, editor of the 1998 Teubner Greek edition, uses the title Apotelesmatiká (biblía), ‘(books on) effects’, which has been followed by recent scholars. Alexander Jones, editor of the Springer publication Ptolemy in Perspective (2010), considers that Ptolemy’s own title remains unknown, but agrees that the term Apotelesmatika is “a credible guess”. This term is variously translated to mean ‘influences’, ‘effects’ or ‘prognostics’; reflecting the theme of work, which is concerned with gaining foreknowledge of the effects of predictable astronomical cycles.

There is no firmly established date for the compilation of the Tetrabiblos, but Ptolemy discloses in his ‘Introductory Address’ that he wrote his astrological treatise after completing his astronomical one: the Almagest. Evidence within the Almagest reveals that the astronomical work could not have been completed before about 145 AD, which demonstrates that Ptolemy wrote the Tetrabiblos towards the end of his life, sometime between completing the Almagest and his death, generally reported to be around 168 A.D.

No original manuscripts of the text have survived; its contents are known from translations, fragments, paraphrased copies, commentaries and later Greek manuscripts. Astrological researcher Deborah Houlding, in an analysis of how specific points agree or vary between different editions, suggests that areas of conflicting details have been affected by three main streams of transmission: manuscripts that have passed through Arabic translation; those based on a paraphrased edition, and manuscripts that are dated four centuries later than the Arabic ones, but which have not undergone translation out of Greek.

An anonymous Greek paraphrase is speculatively attributed to the 5th-century philosopher Proclus. It is often referred to as the Proclus’ Paraphrase although its authenticity is questioned, being described as “very doubtful” by Professor Stephan Heilen. The content of the Paraphrase is close to that of manuscripts of the Tetrabiblos, but it uses simplified text with the aim of providing what Heilen calls “a more easily understandable version of the difficult original work”.

There is no modern critical edition of this text. The oldest extant manuscript is dated to the 10th century and housed in the Vatican Library (Ms. Vaticanus gr.1453, S. X., ff.1–219).[126]: 269 Some of the text of the Paraphrase was published with a Latin translation and Preface by Philipp Melanchthon in Basel, 1554, but this was not widely circulated. A full reproduction with an accompanying Latin translation was made around 1630 by the Vatican scholar Leo Allatius “for his own private gratification” and this was published by the Elzevir typsetters in Leiden, 1635, apparently without Allatius’s knowledge or consent.

Allatius’ Latin translation was used as the source of all English translations of the Tetrabiblos prior to the Robbins’ edition of 1940. These include translations made by John Whalley (1701); the Whalley “corrected edition” made by Ebenezer Sibly and his brother (1786); J.M. Ashmand (1822); James Wilson (1828); and other 19th-century privately circulated manuscripts such as that of John Worsdale.

Although no copies of Ptolemy’s original manuscript remain, there are other ancient works, such as Hephaistio’s Apotelesmatics I, which describe or reproduce some of its passages. These have been used to help verify disputed areas of content.

The oldest fairly complete Greek manuscript of the text (rather than the paraphrased edition made of it) is dated to the 13th century. Two or three others are dated to the 14th century but most are dated to the 15th and 16th centuries. In the ‘Introduction’ to his 1940’s translation, Frank Eggleston Robbins reported the existence of at least 35 manuscripts containing all or a large part of the Tetrabiblos in European libraries.

In 1940, a Greek critical edition was published by Teubner, in Germany, based on the unpublished work of Franz Boll which was completed by his student Emilie Boer. Robbins expressed regret at not being able to refer to this in the preparation of his English translation.

In 1994 the ‘Boll-Boer’ edition became the basis of a serialised English translation by Robert Schmidt, published by Project Hindsight. The ‘Translator’s Preface’ was critical of Robbins’ understanding of some of the “conceptual issues involved” and argued the need for a new English translation which recognised the “probable superiority of the Teubner text edited by Boll and Boer in 1940”.

The most recent critical edition of the Greek text was made by the German scholar Professor Wolfgang Hübner, and published by Teubner in 1998. Based on 33 complete and 14 partial manuscripts, Hübner also incorporated the unpublished notes of Boer and the reasoning given in the Robbins and Boll-Boer editions. This is now considered the authoritative edition. A reviewer’s comment in The Classical Review declares of it “Progress over previous editions is evident on virtually every page”.

In addition to the Arabic commentary on the Tetrabiblos made by Ali ibn Ridwan (Haly) in the 11th century, significant attention is given to an anonymous Greek Commentary, which has older, obscure origins. It was written at an uncertain date, in either late antiquity or the Byzantine period. This is also attributed to Proclus, as the presumed author of the Paraphrase, although Heilen has remarked that such an attribution “looks like guesswork”. Houlding has also pointed out that differences in tabulated information presented within the Paraphrase and the Commentary “is a telling argument that both cannot be the work of the same author”.

The Greek Commentary was first printed in 1559 with an accompanying Latin translation by Hieronymus Wolf. This claimed to be based on a heavily corrupted manuscript which required numerous conjectures by a scholarly friend of Wolf, who preferred to remain anonymous rather than face reproaches for “dabbling in this sort of literature”.Wolf’s edition was bound with an Introduction to the Tetrabiblos, attributed (speculatively) to Porphyry, and the scholia of Demophilus.

The purpose of the Commentary was to offer demonstrated illustrations and fuller explanation of the astrological principles described by Ptolemy. Following Wolf’s edition, large passages were incorporated into Latin astrological works which featured extensive collections of example horoscopes. Two notable examples are Jerome Cardan’s Ptolemaei De Astrorvm Ivdiciis (Basel, 1578) and Francisco Junctinus’s Speculum Astrologiae (Lugduni, 1583).

Modern translators continue to make reference to the Hieronymous Wolf Commentary in their explanatory annotations.

Please contact us for more information here